Modernism and Latin America

How did modernism get here? We spoke with Sabrina Moura to discuss whether we were already modern or perhaps we never were

In our last episode, we traced a kind of genealogy of modern art – on one side, the process of industrialization, the idea of progress and technological development, the consolidation of urban centers; on the other, artists who increasingly sought a unique language, who wanted to challenge the traditional precepts of academia, who wanted freedom for new ways of painting. From this combination of elements emerged Impressionism, centered on the figure of Édouard Manet, and with it the trigger for a whole new series of new artistic and aesthetic movements that extended from the last decades of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century. What began with Impressionism unfolded into countless side effects, with the succession of what we call avant-garde movements – different styles that popped up throughout Europe in the following hundred years.

Are we doomed to a culture of repetition?

And here comes our question: What was happening in the meantime in what we call Latin America? What is the role of Latin America in modernity? How did modernist art arrive in Latin America? Did it actually arrive here or were we already, in a way, modern? Or were we never modern? Why do we look so much to Europe as a reference and standard of visuality?

Since the times of European colonization, the main mark of our political, economic and social marginalization has been the absence of Latin America in the history of universal art. According to the perspective of many Eurocentric thinkers, we Latin Americans are doomed to eternally be a “culture of repetition”, reproducing models, and it is not up to us to found or inaugurate aesthetics or movements that could be incorporated into universal art.

The term Latin America itself serves to hinder this view, since it refers broadly to the countries of America, including the Caribbean, whose languages derive from Latin. However, in Suriname, for example, Dutch is spoken, just as in the Bahamas and Jamaica English is spoken. There is also no geographical justification for the term, since we are not talking strictly about the South, since Mexico, for example, is already part of what we call North America. For this reason, this term is now considered very problematic and imprecise, since, in theory, it would create an identity that, in reality, brings together very different countries…

On the other hand, there is a common experience, from Mexico to Argentina, that can unite these very diverse nations: we were all subject to colonial conquests, the enslavement of African peoples, the extermination of local peoples and the imperialism that still maintains the region today – even because the effects of these processes are still felt today, throughout the continent. These are countries with worrying environmental exploitation and intense deforestation; rural producing nations without industrial or service development; regions marked by authoritarianism, populism and brutal inequality – where poverty lives side by side with wealth accumulated in unbelievable proportions.

Walter Mignolo, an important Argentine thinker on the idea of “Latinidad”, says that the “idea” of Latin America is a sad celebration by the “criollo” elites – descendants of Europeans born here – of their inclusion in “modernity”, that is, in the process of technological development of industrialization, urban expansion, rural exodus, and the “erudition” of artists! But the reality is that these elites sank deeper and deeper into the logic of coloniality.

The word “Latinidad” encompassed an ideology that included the identity of the former Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the new order of a modern/colonial European world. When we think that modern art emerged in the mid-19th century, we cannot help but notice that there were still many newly independent countries in the world or that were still colonies – think of including Cuba and Panama and most of the countries in Africa that gained their independence only in the last 40 to 60 years.

The truth is that, for a long time, official art history did not even consider that there could be an independent, living, valid Latin American art. In his text for the first Mercosul Biennial, Frederico Morais recalled an infamous phrase by Henry Kissinger, who was Secretary of State of the United States between 1973–1977: Nothing important can come from the South. History is never made in the South. But we know that this is not true – it was not true, and it continues not to be true.

This narrative is reinforced by the official history of art, which states that modernity arrived in America through artists who – in the absence of art academies, an abundance of collectors and patrons, and interest from the government and the population – traveled to Europe to study and, impacted by the avant-garde movements they witnessed, the exhibitions they visited, and the artists they knew. They returned home carrying these references in their suitcases. In this way, modernity in Latin America, on the one hand, is written as being indebted to European modernity, reiterating this view that we are doomed to repetition, and on the other, as a melting pot of vibrant mixtures, capable of inventing its own modernity.

But is this the correct answer? The truth is that, industrially, Latin America really suffers from the delay in modernization not only due to colonization, but also due to quite retrograde processes of independence in some regions (despite the powerful transformations of Simon Bolívar and José de San Martin).

Historically, we know that the idea of modern art was indeed imported from one side, but it culminates in a contradiction – Latin American modern art is also a first attempt to construct local, regional aesthetic and cultural identities, which would be built not only on European visual standards, but also on revisions of the pre-colonial past, on an idea of national identity, seeking another genealogy for artistic production. European art presupposes itself as universal art, and we can either integrate it as apprentices, or we will be marginalized (as happened for a long time).

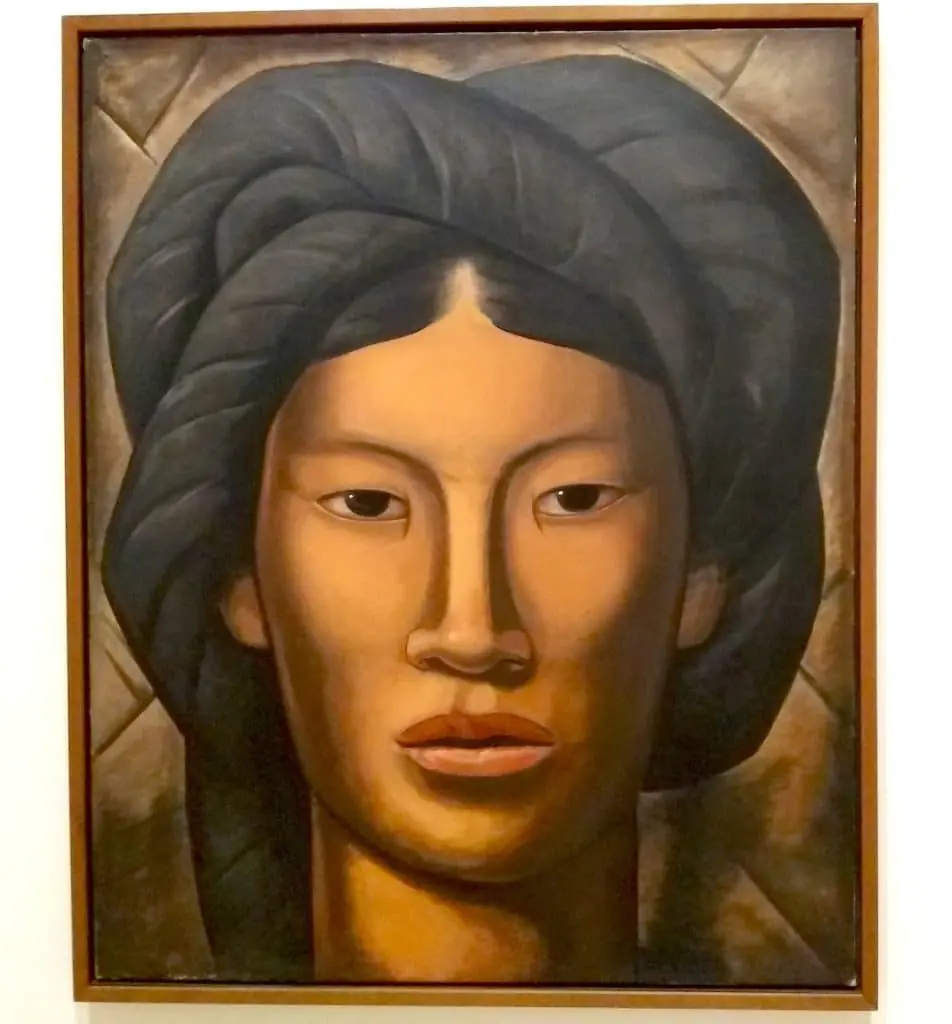

Today, however, it is already possible to trace how European modernity is only a part of history and how we have not only artists, but also art, that is, theories, aesthetics. Theories that do not apply only to the Latin American context, but that can serve as indispensable instruments for understanding the entire process of modern and contemporary art. The reverse path, in fact, is possible! It may have taken us a few decades to catch up with the European avant-garde movement, but that doesn’t mean that what came after is just repetition, imitation, or derivation. There are other challenges in telling this story, though. The thing is: Brazil, Peru, Chile, and Argentina do not share the same antecedents of modernity, modernization, or modernism. According to Nelly Richard, a Chilean researcher and theorist, the development of cultural trends in these and other countries was neither homogeneous nor uniform, and the disposition of each one toward modernity followed regional dynamics of specific, incomparable forces and resistances. Some countries, for example, established greater or lesser degrees of appreciation for inherited indigenous culture – as is visible in Mexican modernity.

Source

- November 28, 2025

Gallery of Cartoon by Diego Pares - Argentina

- November 28, 2025

Gallery of Cartoons by Gilmar Fraga – Brazil 2

- November 28, 2025

How to Draw Birds by Mitch Leeuwe

- November 27, 2025

Gallery of Poster Design by Jorge Mares – Mexico

- November 27, 2025

New Curatorial Discourses in Latin America

- November 27, 2025

Printmaking and its Tradition in Mexico and Chile

- November 27, 2025

Javier Muñoz - Argentina

- November 27, 2025

New Curatorial Discourses in Latin Amer…

- November 27, 2025

Printmaking and its Tradition in Mexico…

- November 26, 2025

Latin American Abstract Painting: From …

- November 26, 2025

The Influence of Brazilian Neo-Concreti…

- November 25, 2025

Graffiti as a tool for social activism …

- November 25, 2025

Street art en São Paulo, Bogotá y Ciuda…

- November 23, 2025

Contemporary Sculpture in South America

- November 22, 2025

Graffiti as a Tool for Social Activism …

- November 22, 2025

Latin American Urban Artists Who Are Se…

- November 20, 2025

The Evolution of Modernism in Latin Ame…

- November 19, 2025

Colombia: Muralism as a Social Voice an…

- November 19, 2025

Brazil: The Creative Power of Urban Art

- November 18, 2025

Visual Arts: History, Languages, and Cu…

- November 18, 2025

Indigenous Art: Characteristics and Typ…

- November 17, 2025

What are the types of AI?

- November 16, 2025

The Importance of Aesthetic Experience …

- November 16, 2025

Art as a Mirror of Culture: Between Tra…

- November 15, 2025

The Influence of Artificial Intelligenc…

- November 15, 2025

The Evolution of Digital Art in the 21s…

- November 13, 2025

Urban Art in Latin America: A Visual Re…

- August 29, 2023

The history of Bolivian art

- February 19, 2024

Analysis and meaning of Van Gogh's Star…

- January 28, 2024

Culture and Art in Argentina

- September 25, 2023

What is the importance of art in human …

- September 23, 2023

What is paint?

- August 10, 2023

14 questions and answers about the art …

- August 23, 2023

The 11 types of art and their meanings

- September 23, 2023

Painting characteristics

- August 30, 2023

First artistic manifestations

- January 12, 2024

10 most beautiful statues and sculpture…

- September 23, 2023

History of painting

- March 26, 2024

The importance of technology in art1

- March 26, 2024

Cultural identity and its impact on art…

- August 16, 2023

The 15 greatest painters in art history

- April 06, 2024

History of visual arts in Ecuador

- April 02, 2024

History visual arts in Brazil

- October 18, 2023

History of sculpture

- July 13, 2024

The impact of artificial intelligence o…

- August 13, 2023

9 Latino painters and their great contr…

- November 21, 2024

The Role of Visual Arts in Society

- February 19, 2024

Analysis and meaning of Van Gogh's Star…

- August 13, 2023

9 Latino painters and their great contr…

- August 23, 2023

The 11 types of art and their meanings

- August 10, 2023

14 questions and answers about the art …

- August 29, 2023

The history of Bolivian art

- August 27, 2023

15 main works of Van Gogh

- January 28, 2024

Culture and Art in Argentina

- November 06, 2023

5 Latin American artists and their works

- September 23, 2023

Painting characteristics

- September 23, 2023

What is paint?

- September 25, 2023

What is the importance of art in human …

- March 26, 2024

Cultural identity and its impact on art…

- August 30, 2023

First artistic manifestations

- December 18, 2023

10 iconic works by Oscar Niemeyer, geni…

- January 20, 2024

What is the relationship between art an…

- January 12, 2024

10 most beautiful statues and sculpture…

- October 30, 2023

Characteristics of Contemporary Art

- August 24, 2023

The most famous image of Ernesto "Che" …

- August 22, 2023

What are Plastic Arts?

- May 26, 2024