José María Velasco: The Landscape Artist Who Painted Mexico for the World

Who is the first Latin American artist to whom the National Gallery in London dedicated an exhibition?

The Mexican José María Velasco was the foremost artist of a type of landscape painting from his country: he made Mexican geography the subject of his painting.

"José María Velasco, Mexican. I paint Mexico."

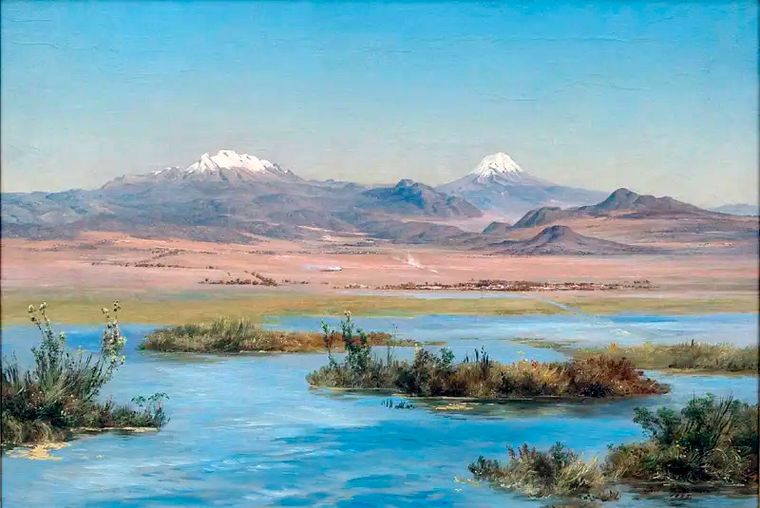

This is how he signed what was considered his masterpiece, "View of the Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel," in the lower right corner of 1877.

He had painted it explicitly to send it to the 1878 Paris World's Fair.

He seems to have wanted to make it clear to the world not merely who he was, but that what they were seeing was this young country that just 10 years earlier had freed itself from the Austrian Maximilian of Habsburg, whom Napoleon III had installed as Emperor of Mexico to establish a satellite empire in the Americas.

Perhaps he shouldn't have worried; after all, by then he was already well-known, both in Mexico and abroad.

In fact, he had received numerous awards, one of them from Emperor Maximilian in 1864, as well as the gold medal at the Mexican National Exhibitions of Fine Arts in 1874 and 1876, and the gold medal at the Philadelphia International Exposition.

The 1877 painting was so successful in Paris that he was asked to make copies, and one of them was presented to Pope Leo XIII.

It wasn't the only time he triumphed in the French capital.

At the 1889 World's Fair, he presented 68 of his works and, he wrote in a letter:

"...my paintings have had a great impact, they are quite pleasing, and they were surprised to see that these works, which they judge to be of considerable merit, can be painted in Mexico."

"Yesterday I received the Knight of the Legion of Honor Decoration. It is a reward that honors me greatly, and I consider it a great distinction."

Thus, he accumulated awards, praise, and admiration, not least from his students at the National School of Fine Arts (ENBA), where he taught artists such as Diego Rivera, from 1868 to 1903.

And yet, during his later years, he was not so present.

So much so that his death was not recorded in the Mexican press until two days later, as journalist Kathya Millares noted in Nexos.

One of the two newspapers that reported his death was El Imparcial, giving little more than details of his funeral.

The newspaper elaborated further, noting that "The elderly Mr. Velasco had brought prestige to national art, having won top diplomas and prizes in highly acclaimed exhibitions held in Paris, Vienna, Madrid, Italy, Milan, Chicago, and other cities."

However, this relative oblivion was quickly remedied by the authorities with exhibitions, celebrations, and commemorations.

Soon, they secured him a distinguished place in official culture, not only for his artistic talent but also for helping to cement Mexican identity.

To this day, his works are known in his country, although those who find them familiar may not know who painted them.

But outside of Mexico, he is little, if ever, remembered at all.

Why? asked British artist Dexter Dalwood, who lives in Mexico and became interested in Velasco's painting.

He then proposed to the National Gallery in London, with which he has a long relationship, to hold an exhibition with him as co-curator.

The idea was welcomed.

"By happy coincidence, the event marks 200 years of diplomatic relations between Mexico and the United Kingdom," Daniel Sobrino Ralston, also the exhibition's curator, told BBC Mundo.

That wasn't the only happy coincidence.

"Velasco is a very eminent painter of 19th-century Mexico, and we thought he fit very well with the art we have at the National Gallery, especially with a series of exhibitions we've done on national landscapes from that century."

Until now, he explains, "those that haven't been European have been by artists from English-speaking countries."

Velasco became the exception in that series of 19th-century landscape artists.

More than that: although the prestigious gallery has acquired and exhibited works by Latino and Latin American artists, "this is the first time the National Gallery has dedicated an exhibition to a Latin American artist," Sobrino points out.

Thus, more than a century after his death, Velasco earned another distinction.

Always romantic

José María Tranquilino Francisco de Jesús Velasco y Gómez-Obregón was born in Temascalcingo in 1840, the same year that Claude Monet, the initiator and leader of Impressionism, was born in France.

Despite being part of the same generation of artists, while Europeans were revolutionizing art, Velasco was doing the opposite.

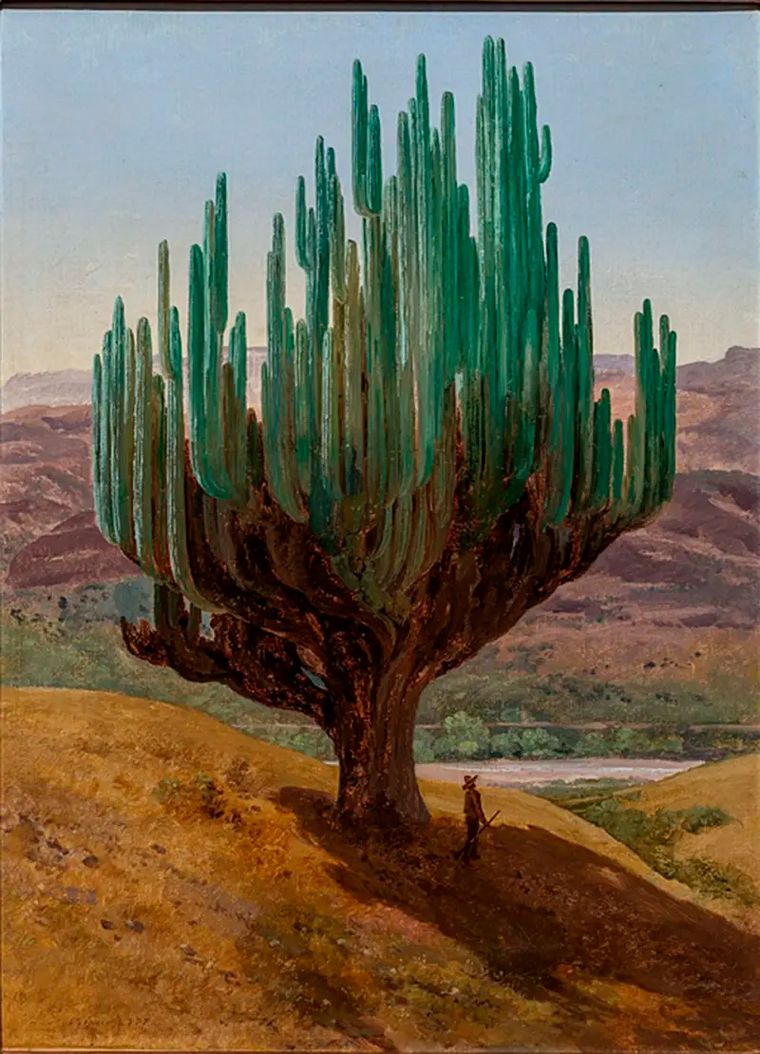

"The Baths of Nezahualcoyotl," 1878.

"He was not an innovator," notes the curator.

"Tiene su estilo, su objetivo, y no cambia mucho. Mantiene el estilo romático de su maestro Landesio, pero llega a un estilo un pocEse maestro, el pintor italiano Eugenio Landesio, enseñaba en la Academia de San Carlos, la primera academia de Bellas Artes en el continente americano (ahora parte de la UNAM), y dejó una marca indeleble en Velasco.

Su obra siempre mantuvo ese acento romántico que busca exaltar la naturaleza, en línea con el movimiento artístico de la última parte del siglo XIX que estaba dando sus últimos coletazos.

Como concordaba con el canon del momento, mientras que las pinturas de los impresionistas eran rechazadas en las exposiciones del Salón en Francia, las de Velasco eran aceptadas, y laureadas.

"Es un artista muy sobrio, muy serio", indica Sobrino.

Su México

Velasco sazonó ese academicismo de origen europeo con toques de la tradición y el paisaje de su país.

E hizo precisamente lo que declaró en esa esquina de esa pintura: pintó México.

Particularmente su México, pues, así como no exploró otros caminos en el arte, a diferencia del común de los paisajistas, Velasco no era muy dado a partir con sus pinceles y pinturas a lugares distantes en busca de horizontes desconocidos.

Viajó poco y ni siquiera pintó en su periplo más largo, a la Exposición Universal de 1889, cuando recorrió Europa durante un año.

Según su biógrafo Luis Islas García, de esa experiencia cosechó "fotografías de los principales monumentos; extrañeza por el Impresionismo; alarma por las costumbres y una publicidad merecida".

"La extrañeza, mejor, el desdén que tuvo por la pintura que conoció en Europa le salvó de influencias quizá perniciosas, y siguió pintando con su estilo propio, sin preocuparse de los pintores extranjeros", añadió ese autor.

En tierras remotas, conoció la nieve, pero en su obra solamente aparece en los picos de los volcanes Popocatépetl e Iztaccíhuatl. También conoció el mar, pero sólo lo pintó una vez.

Fuente

- February 22, 2026

Blanton’s New “Paper Trails” Exhibition Explores Prints

- February 22, 2026

Board of Peace...

- February 22, 2026

Painting with Watercolour by David Howell

- February 21, 2026

Mexico Exhibition: Gelman-Santander Collection of Modern Art

- February 21, 2026

The Art, Science, and Craft of Great Landscape Photography

- February 22, 2026

Blanton’s New “Paper Trails” Exhibition…

- February 21, 2026

Mexico Exhibition: Gelman-Santander Col…

- February 19, 2026

ARCO Madrid to Celebrate 45 Years with …

- February 17, 2026

Seven Free Art Exhibitions to Enjoy in …

- February 14, 2026

Remedios Varo and the Enduring Legacy o…

- February 10, 2026

Latin American Art Cultural Encounter f…

- February 08, 2026

A Bridge Between Latin American Art and…

- January 27, 2026

The exhibitions "From Tàpies to Siqueir…

- January 19, 2026

The Pulse of Art, Design, and Culture R…

- January 19, 2026

The Argentine museum celebrates 25 year…

- January 08, 2026

Latin American Pavilion Among the New A…

- January 07, 2026

Material Art Fair 2026

- January 05, 2026

The Latin American Pavilion Marks a Mil…

- December 31, 2025

the 10 million-dollar sales of 2025

- December 30, 2025

MALBA Doubles Collection and Reposition…

- December 29, 2025

The FEMSA Collection will celebrate its…

- December 25, 2025

“Ancestral Artist”: A Look at the Craft…

- December 25, 2025

Winner of the 13th Most Important Conte…

- December 25, 2025

Malba Acquires the Daros Latinamerica C…

- December 24, 2025

2026, a Key Year in Cultural Exchange B…

- October 08, 2023

Illustrations reflect the brutal Israel…

- December 25, 2023

The jury statement of the Iran-Brazil F…

- March 21, 2024

The history of art in Palestine

- July 29, 2023

History of Caricature in Brazil

- September 01, 2023

Neural Filters in new photoshop 2023

- May 22, 2025

Brady Izquierdo’s Personal Exhibition O…

- April 20, 2024

Poignant Image of Grief Wins Mohammed S…

- February 18, 2024

7 Ways to Understand What Visual Arts A…

- October 21, 2023

Erick Meyenberg and Tania Ragasol at th…

- May 15, 2024

Eleven murals for Gaza painted across t…

- June 29, 2024

Exhibition at Centro MariAntonia contra…

- March 30, 2024

illustration websites in Latin America

- March 14, 2024

museum of statue of van gogh

- August 09, 2023

Venezuela mural expresses solidarity wi…

- May 25, 2025

Bordalo II to hold exhibition in Paris …

- March 15, 2024

museum of sculpture of Salvador Dali

- May 20, 2024

Latin American Festival of Performing A…

- June 24, 2024

The urban art that lives in Lima

- July 30, 2024

The artist from San Luis Mirta Celi rep…

- August 23, 2024

Ai is not our future-Procreate

- May 15, 2024

Eleven murals for Gaza painted across t…

- February 18, 2024

7 Ways to Understand What Visual Arts A…

- January 02, 2025

13 commemorations that will mark the cu…

- October 17, 2023

The influence of Latin American artists…

- February 03, 2024

THE HISTORY OF NAIF ART

- July 02, 2024

One of the largest urban art galleries …

- November 17, 2023

Fernando Botero's work is booming after…

- October 08, 2023

Illustrations reflect the brutal Israel…

- July 29, 2023

Piracicaba International Humor Exhibiti…

- December 25, 2023

The jury statement of the Iran-Brazil F…

- November 06, 2023

Heba Zagout: Palestinian artist murdere…

- December 10, 2023

Sliman Mansour and Palestinian art on t…

- March 14, 2024

museum of statue of van gogh

- February 01, 2025

A maior exposição de Botero em Barcelona

- March 21, 2024

The history of art in Palestine

- July 20, 2024

First International Mail Art Biennial 2…

- April 20, 2024

Poignant Image of Grief Wins Mohammed S…

- October 30, 2023

Palestinian turns images of the Gaza co…

- September 01, 2023

Neural Filters in new photoshop 2023

- February 08, 2024