Palestinian Art Emerging Under Siege in Gaza

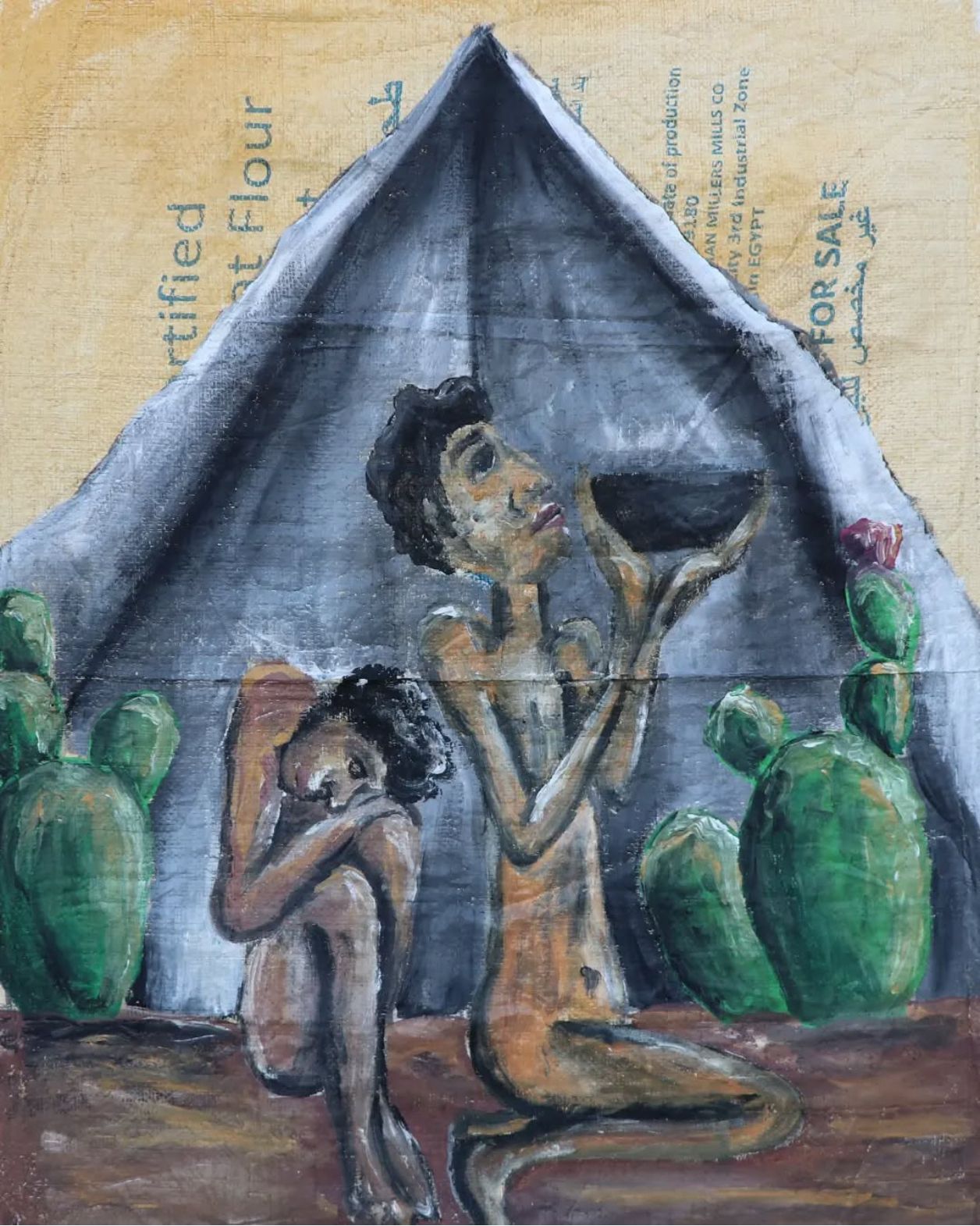

United Nations bags, stones under rubble, empty boxes: almost any surface is suitable for a new generation of Palestinian artists sheltering in tents. Painting, for them, is a way to protect what still lives.

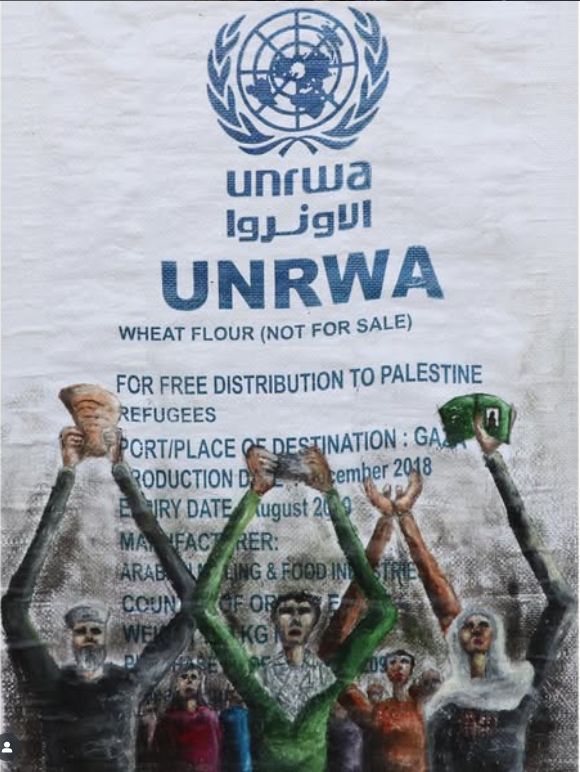

Hussein al-Jerjawi is eighteen years old and has been displaced five times by Israeli attacks. After missing an entire school year, like thousands of teenagers whose education was suspended by the bombing, he chose a way forward: painting on empty flour bags and raising funds under the do-it-yourself ethic. In them, he portrays families baking bread, refugees pleading for dignity with their arms raised, and women and children turned into chess pawns. In Gaza, where life is played out like a game without rules, art offers a psychological refuge under the fire. Through drawing and painting, some Palestinians relieve their minds from the incessant noise and write, perhaps unintentionally, their memoirs. “I’m making art right now because it’s the only way to communicate the suffering and resilience of our people,” al-Jerjawi told GACETA.

In the late 1980s, artist Suleiman Mansour, a central figure of the First Intifada, began experimenting with mud, henna, clay, and straw. Non-traditional plastic materials. Elements that sprouted from the Palestinian earth. The metaphor was clear: if national symbols were stripped in the war, they would have to be rebuilt with input from their own environment. Today, under a longer and more atrocious siege, this aesthetic principle lives on in Palestinian artists. Instead of imported pigments and canvases, the artists work with medicine containers, notebooks provided by the UN, and stones salvaged from the rubble. It’s their response to the systematic attempt to erase their culture. As multidisciplinary artist Shareef Sarhan said: “Each painting is a document that tells the world that we are alive, that we dream, and that we cling to our roots.”

Nineteen-year-old Ibrahim Mahna paints on boxes of humanitarian aid. Where cans of fish once stood, there are now human figures with sunken eyes and open mouths. There are also tents: those fragile fabric shelters surrounded by palm trees that, for a portion of the population, are all that remains. "They don't protect from the wind or from grief. But I paint them so they don't disappear," Mahna told Al Jazeera.

From this forced ecosystem—camps with shelters made of nylon tarps, mud thickened by storms, hands raising vessels as offerings—poetic images emerge. In Gaza, creation is born, once again, from the elements. Scarcity not only drives ingenuity: it builds an aesthetic, redefines the notion of home, and transforms waste into a testament to life. Each work bears the material imprint of the siege. The artists don't erase the UN seals from the bags: they integrate them. There is no deeper story than that written on the remains of what saved a body.

The need to create under siege, to redefine relief materials, and to sustain roots in the midst of displacement has ancient roots. As art historian Adila Laïdi-Hanieh explains, Palestinian visual production did not grow as a formal movement or a stable tradition, but rather as a set of scattered impulses. In the 18th century, some artists linked to the Orthodox Church began painting icons influenced by Byzantine art. Later, several of them trained with Russian monks in the Holy Land, developing a devotional style that was interrupted by the conflicts of the 20th century. In 1948, with the Nakba and the forced expulsion of 700,000 people following the creation of the State of Israel, the possibility of consolidating a local aesthetic was truncated.

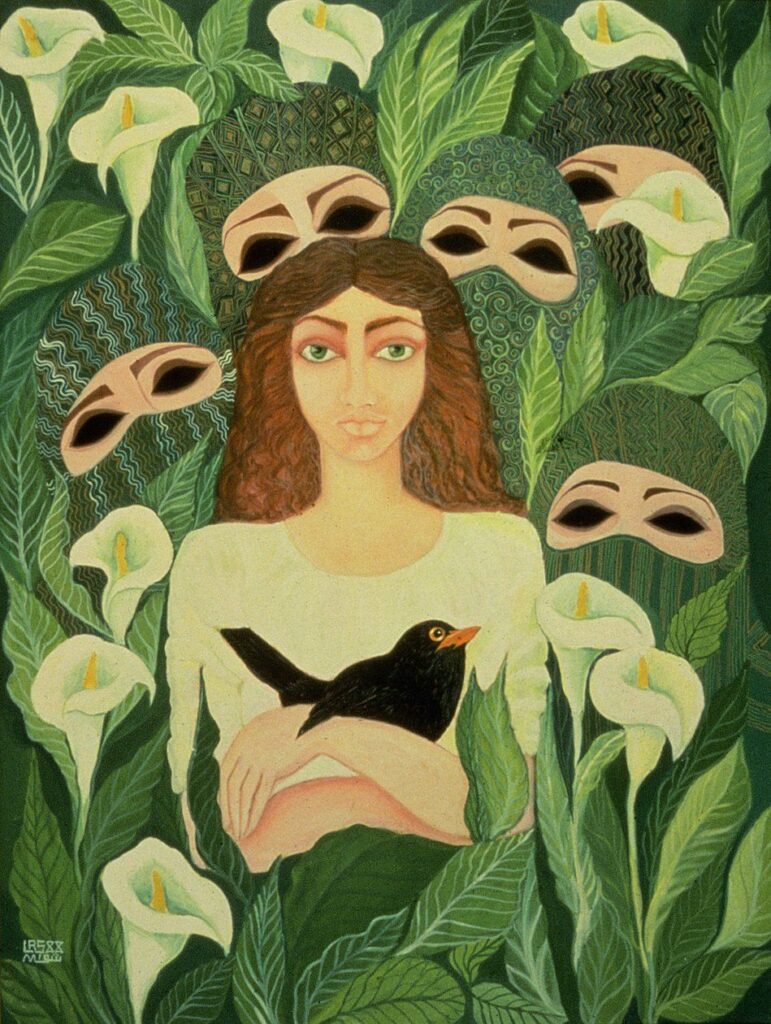

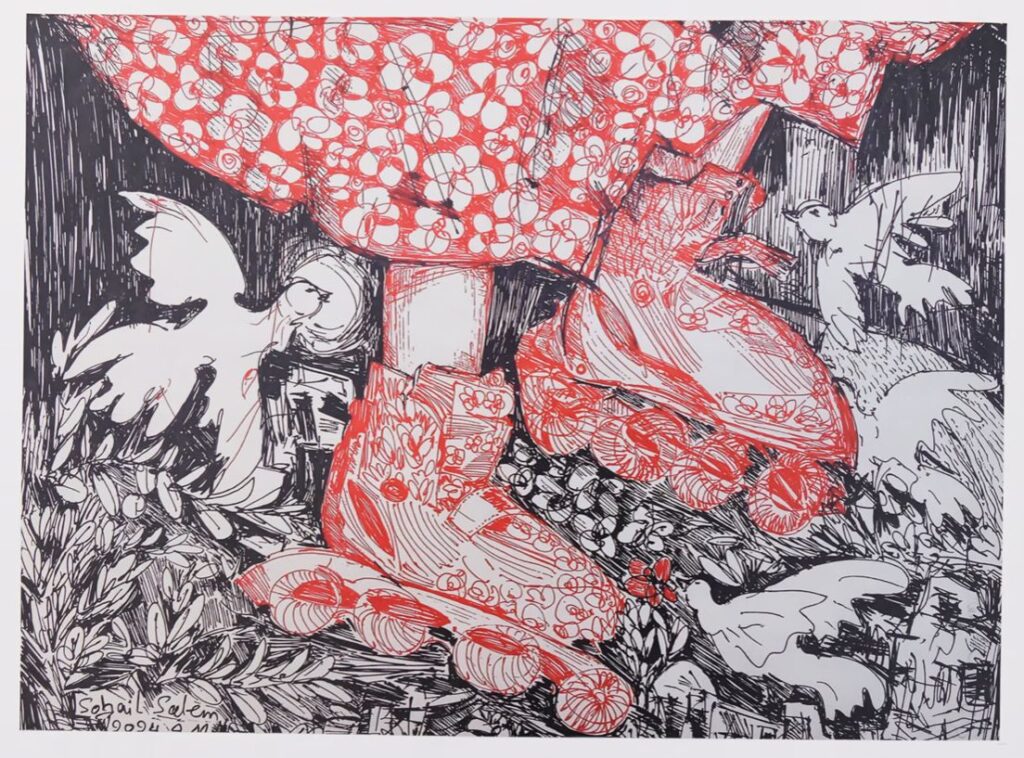

Since then, Palestinian art has developed amidst diasporas and discontinuities. In the 1960s and 1970s, a new generation of artists, mostly born in refugee camps, began using drawing, painting, and printmaking as tools of memory and forms of celebrating their identity. The increasingly politicized exhibitions in the West Bank and Gaza did not sit well with the Israeli side. In response, in 1980, the State of Israel banned ideologically charged exhibitions and the incorporation of the four colors of the Palestinian flag in a single work, according to an article from the University of San Diego. Hence the popularization of the watermelon, which shares the same Palestinian national colors, in local art.

Beginning in the 1990s, Palestinian art entered a period of expansion and risk. It became more conceptual, more multimedia, less patriarchal. Some critics called this period "the tense present" and described it as a display of intimate explorations of the landscapes of occupation and exile. Samia Halaby, a pioneer of Arab abstract painting, turned geometry into a field of emotional liberation, while Laila Shawa used silkscreen printing to denounce the oppression of women under fire. Both demonstrated that art could be experimental without losing its political edge.

Now, under the cramped tents of displaced persons, some artists in their early twenties have returned to drawing and painting. This return is not meant in a nostalgic sense: it can be seen as a new conceptual shift in local art. In an era filled with devastating photos—more than 57,000 Palestinians have died since the start of the Israeli offensive in October 2023—the repetition of stark scenes can begin to chill our capacity for emotion and action. If you type the word "Gaza" into Google, you'll see destruction on all scales: a land in ruins, grieving faces, hands clutching dead bodies. Existence reduced to its most unbearable expression. Art, on the other hand, pauses and rescues what still connects. I see drawings of families gathered around pots of hot food and children peering curiously over a fence, and I think these images seek to remind us that a dignified life also needs to be represented. Hussein al-Jerjawi told me he paints his friends and family because they are the faces that keep him going.

In Gaza, there is no formal art circuit today. What there are are tenacious and scattered efforts to create work amid the emergency. Although the cultural infrastructure has been pulverized—al-Jerjawi tells me that most spaces were destroyed and artistic resources have almost disappeared—the war has not halted the production or mobility of art. Many pieces have left the besieged territory for neighboring Jordan. During the first half of this year, the Darat al-Funun Center hosted the "Under Fire" exhibition, featuring works created in Gaza during the harshest months of the siege. Cities such as London, Barcelona, Chicago, Zurich, and Hiratsuka have also hosted exhibitions featuring works by Gazan artists.

This international expansion of Palestinian art reveals a shift: artists are not only seeking to represent and denounce, they are seeking global connection. On his Instagram account, Hussein al-Jerjawi, the painter who works on empty flour sacks, accompanies his posts with an invitation: to print his pieces, distribute them, paste them, and, if possible, contribute financially so his family can afford the essentials. He isn't necessarily seeking curatorial validation, but rather human solidarity and institutional trust in what he's building. His greatest desire now is to win a scholarship so he can leave Gaza. Art, in this context, ceases to be merely an object of contemplation and becomes a networked connection, circulating as nourishment for a community that believes life cannot revolve around survival.

As part of this same network of connections now being woven, the new generation of local artists creates and, at the same time, teaches. They gather children to name what's happening to them on blank sheets of paper. Sometimes it's a drawing of a destroyed house. Other times, many times, it features parks with flowers, trees, and animals where they run free. In this way, they contain the visceral reaction of loss and experience a space for concentration, reverie, and relief. At a time when school isn't open and psychological therapy isn't available, many children are learning through art to connect with their emotions and narrate their stories.

Palestinian art has forged its own path of symbolic survival. If the world decides to pay attention and ask itself questions, it might be worth starting with these: What conversations can art open when it doesn't show lacerated bodies in close-up, but rather community rituals? Can international galleries and museums do more than exhibit? Beyond sharing outrageous images on social media, are we willing to reach into our pockets to support artists who, with every work sold, buy bread, medicine, and blankets to protect them from the cold? The underlying question is this: will the network of solidarity that is currently being built from tents survive when the drones and cameras are turned off? Perhaps Palestinian artists don't need grand gestures, but rather others, on the other side of the world, who commit to their struggle in their own way. If Hussein al-Jerjawi could send a WhatsApp voice note that reached the entire world, it would say only this: "Stop the war. Bring food.

Source

- January 27, 2026

Aztecs in the Empire City: “The People Without History” in The Met

- January 27, 2026

The Evolution of Art: From Classical to Digital

- January 27, 2026

What are Visual Arts and Why Do They Matter Today?

- January 27, 2026

Selected Illustration Gallery of Venezuelan Artists

- January 27, 2026

Selected Caricature Gallery of Cuban Artists

- January 26, 2026

Bolivia Poster Biennial (BICeBé 2013)

- January 26, 2026

Selected Gallery of Paintings by Peruvian Artists

- January 26, 2026

Selected Gallery of Watercolor Paintings by Peruvian Artists

- January 27, 2026

The exhibitions "From Tàpies to Siqueir…

- January 19, 2026

The Pulse of Art, Design, and Culture R…

- January 19, 2026

The Argentine museum celebrates 25 year…

- January 08, 2026

Latin American Pavilion Among the New A…

- January 07, 2026

Material Art Fair 2026

- January 05, 2026

The Latin American Pavilion Marks a Mil…

- December 31, 2025

the 10 million-dollar sales of 2025

- December 30, 2025

MALBA Doubles Collection and Reposition…

- December 29, 2025

The FEMSA Collection will celebrate its…

- December 25, 2025

“Ancestral Artist”: A Look at the Craft…

- December 25, 2025

Winner of the 13th Most Important Conte…

- December 25, 2025

Malba Acquires the Daros Latinamerica C…

- December 24, 2025

2026, a Key Year in Cultural Exchange B…

- December 23, 2025

Sacred Art Celebrates Christmas Through…

- December 22, 2025

MACA Inaugurates Exhibitions of Fontana…

- December 20, 2025

Costantini Acquires the Daros Collectio…

- December 17, 2025

ARCOmadrid Announces Participating Gall…

- December 17, 2025

Eduardo Costantini Acquired a Collectio…

- December 15, 2025

From Chile to Gaza: «Palestine Cries,»

- December 15, 2025

Latin American Artists MACLA and Montal…

- October 08, 2023

Illustrations reflect the brutal Israel…

- December 25, 2023

The jury statement of the Iran-Brazil F…

- March 21, 2024

The history of art in Palestine

- July 29, 2023

History of Caricature in Brazil

- September 01, 2023

Neural Filters in new photoshop 2023

- April 20, 2024

Poignant Image of Grief Wins Mohammed S…

- May 22, 2025

Brady Izquierdo’s Personal Exhibition O…

- June 29, 2024

Exhibition at Centro MariAntonia contra…

- February 18, 2024

7 Ways to Understand What Visual Arts A…

- October 21, 2023

Erick Meyenberg and Tania Ragasol at th…

- May 15, 2024

Eleven murals for Gaza painted across t…

- March 30, 2024

illustration websites in Latin America

- August 09, 2023

Venezuela mural expresses solidarity wi…

- March 14, 2024

museum of statue of van gogh

- May 25, 2025

Bordalo II to hold exhibition in Paris …

- March 15, 2024

museum of sculpture of Salvador Dali

- May 20, 2024

Latin American Festival of Performing A…

- January 23, 2025

Art Palm Beach 2025

- March 18, 2025

Works by Cuban Artist Eduardo Abela in …

- January 04, 2025

Material Art Fair 2025

- May 15, 2024

Eleven murals for Gaza painted across t…

- February 18, 2024

7 Ways to Understand What Visual Arts A…

- January 02, 2025

13 commemorations that will mark the cu…

- October 17, 2023

The influence of Latin American artists…

- February 03, 2024

THE HISTORY OF NAIF ART

- July 02, 2024

One of the largest urban art galleries …

- November 17, 2023

Fernando Botero's work is booming after…

- October 08, 2023

Illustrations reflect the brutal Israel…

- July 29, 2023

Piracicaba International Humor Exhibiti…

- December 25, 2023

The jury statement of the Iran-Brazil F…

- November 06, 2023

Heba Zagout: Palestinian artist murdere…

- December 10, 2023

Sliman Mansour and Palestinian art on t…

- March 14, 2024

museum of statue of van gogh

- February 01, 2025

A maior exposição de Botero em Barcelona

- March 21, 2024

The history of art in Palestine

- July 20, 2024

First International Mail Art Biennial 2…

- April 20, 2024

Poignant Image of Grief Wins Mohammed S…

- October 30, 2023

Palestinian turns images of the Gaza co…

- September 01, 2023

Neural Filters in new photoshop 2023

- February 08, 2024