Who is the Mexican José María Velasco

Who is the Mexican José María Velasco, the first Latin American artist to whom the National Gallery in London dedicated an exhibition?

"José María Velasco, Mexican. I Paint Mexico."

This is how he signed what was considered his masterpiece, "View of the Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel," in 1877, in the lower right corner.

He had painted it explicitly to send it to the 1878 Paris World's Fair.

He seems to have wanted to make it clear to the world not merely who he was, but that what they were seeing was this young country that just 10 years earlier had freed itself from the Austrian Maximilian of Habsburg, whom Napoleon III had installed as Emperor of Mexico to establish a satellite empire in the Americas.

In fact, he had received numerous awards, one of them from Emperor Maximilian in 1864, as well as the gold medal at the National Exhibitions of Fine Arts in Mexico in 1874 and 1876, and the gold medal at the Philadelphia International Exposition.

The 1877 painting was so successful in Paris that he was asked to make copies, and one of them was presented to Pope Leo XIII.

This was not the only time he triumphed in the French capital.

At the 1889 Universal Exposition, he presented 68 of his works and, he wrote in a letter:

"...my paintings have had a great impact, they are quite pleasing, and they were surprised to see that these works, which they consider quite meritorious, can be painted in Mexico."

"Yesterday I received the Decoration of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. It is a reward that honors me greatly, and I consider it a great distinction."

Thus, he accumulated awards, praise, and admiration, not least from his students at the National School of Fine Arts (ENBA), where he taught artists such as Diego Rivera, from 1868 to 1903.

And yet, during his later years, he was less present.

So much so that his death wasn't recorded in the Mexican press until two days later, as journalist Kathya Millares noted in Nexos.

One of the two newspapers that reported his death was El Imparcial, giving little more than details of his funeral.

The newspaper elaborated further, noting that "The elderly Mr. Velasco had brought prestige to national art, having won the first diplomas and prizes in highly acclaimed exhibitions held in Paris, Vienna, Madrid, Italy, Milan, Chicago, and elsewhere."

However, this relative neglect was quickly remedied by the authorities with exhibitions, celebrations, and commemorations.

Soon, he was assured a distinguished place in official culture, not only for his artistic talents but also for helping to cement Mexican identity.

To this day, his works are well-known in his country, although those who find them familiar may not know who painted them.

But outside of Mexico, he is little, if ever, remembered.

Why? wondered British artist Dexter Dalwood, who lives in Mexico and became interested in Velasco's painting.

He then proposed to the National Gallery in London, with which he has a long relationship, to hold an exhibition with him as co-curator.

The idea was welcomed.

"By happy coincidence, the event marks 200 years of diplomatic relations between Mexico and the United Kingdom," Daniel Sobrino Ralston, also the exhibition's curator, told BBC Mundo.

That wasn't the only happy coincidence.

"Velasco is a very eminent painter of 19th-century Mexico, and we think he fit very well with the art we have at the National Gallery, especially with a series of exhibitions we've done on national landscapes from that century."

Until now, he explains, "those that haven't been European have been by artists from English-speaking countries."

Velasco became the exception in that series of 19th-century landscape artists.

More than that: although the prestigious gallery has acquired and exhibited works by Latin American and Latin American artists, "this is the first time the National Gallery has dedicated an exhibition to a Latin American artist," Sobrino points out.

Thus, more than a century after his death, Velasco earned another distinction.

Always romantic

José María Tranquilino Francisco de Jesús Velasco y Gómez-Obregón was born in Temascalcingo in 1840, the same year that Claude Monet, the initiator and leader of Impressionism, was born in France.

Despite being part of the same generation of artists, while Europeans were revolutionizing art, Velasco did the opposite.

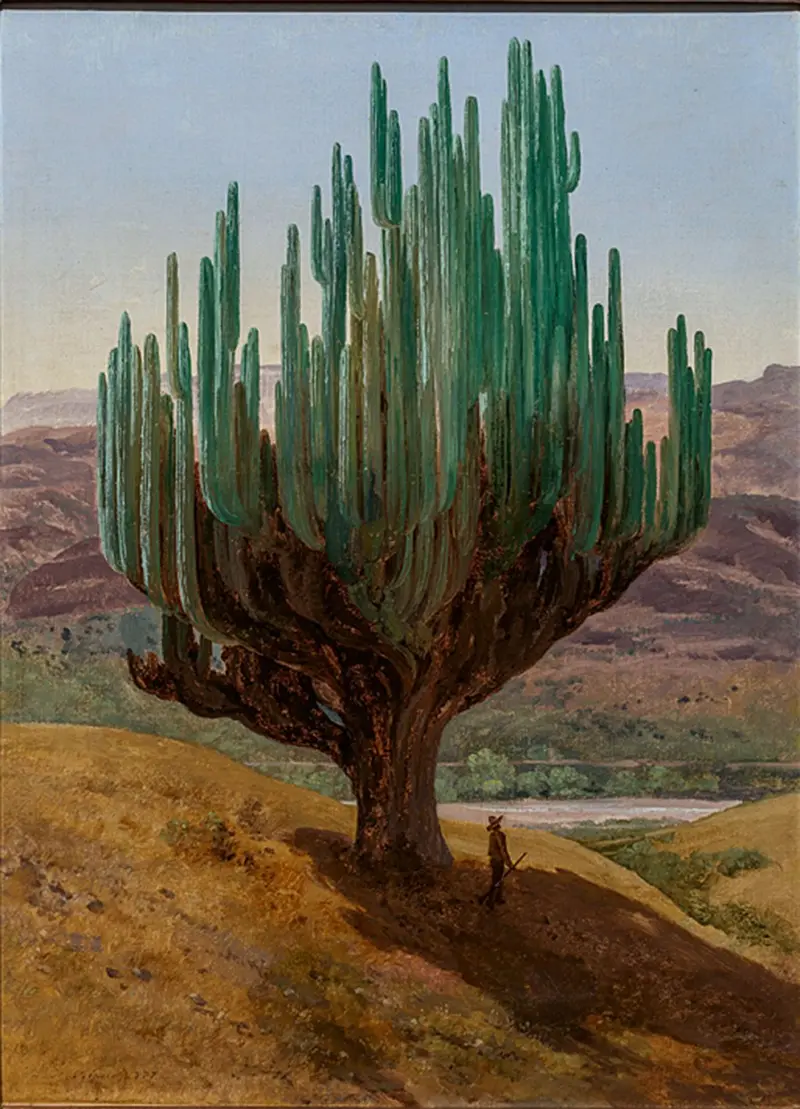

"The Baths of Nezahualcoyotl," 1878.

"He was not an innovator," notes the curator.

"He has his style, his objective, and he doesn't change much. He maintains the romantic style of his teacher Landesio, but achieves a slightly more realistic, objective, and scientific style."

That teacher, the Italian painter Eugenio Landesio, taught at the Academy of San Carlos, the first academy of Fine Arts in the Americas (now part of the UNAM), and left an indelible mark on Velasco.

His work always maintained that romantic accent that seeks to exalt nature, in line with the artistic movement of the latter part of the 19th century, which was in its final stages.

As it was in keeping with the canon of the time, while the Impressionists' paintings were rejected at the Salon exhibitions in France, Velasco's were accepted and awarded prizes.

"He is a very sober, very serious artist," Sobrino notes.

His Mexico

Velasco seasoned that academicism of European origin with touches of the tradition and landscape of his country.

And he did precisely what he declared in that corner of that painting: he painted Mexico.

Particularly his Mexico, because, just as he did not explore other avenues in art, unlike most landscape artists, Velasco was not given to setting off with his brushes and paints to distant places in search of unknown horizons.

He traveled little and didn't even paint on his longest tour, the 1889 World's Fair, when he toured Europe for a year.

According to his biographer, Luis Islas García, from that experience he gained "photographs of the main monuments; awe of Impressionism; alarm at the customs; and well-deserved publicity."

"The awe, or rather, the disdain he felt for the painting he encountered in Europe saved him from perhaps pernicious influences, and he continued painting in his own style, without worrying about foreign painters," the author added.

In remote lands, he encountered snow, but in his work it only appears on the peaks of the Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl volcanoes. He also encountered the sea, but only painted it once.

Panoramic view of the well-known Cabrío Hill, located in the San Ángel area.

Image source: National Museum of Art, INBAL, Mexico City

Caption: "El Cabrío de San Ángel," 1863.

Clearly, what inspired him infinitely was his surroundings, from the details of the topography, flora, and fauna, to the magnificent and inexhaustible panoramas, as well as the changes brought about by humans, including the arrival of industrialization.

Those humans, however, are often absent.

"The human figure only appears when it needs to underline the desolation or solitary grandeur of nature, in the midst of which man is always an intruder," observed the poet, essayist, and Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz in 1942.

It should be noted that Paz did not have a very kind opinion of the painter.

"Cold, rigorous, insensitive, and lucid, JMV is only half of the genius. But it is a half that warns us of the dangers of pure sensuality and imagination alone," he concluded.

However, the appreciation of art changes depending on the moment and the eyes that view it.

Many appreciate not only the record he left of an era, but also the majesty of his landscapes, as well as the subtleties in tones and light, and the way he captured layers of history, celebrating Mexico's mixed identity.

"There is a kind of intellectual project that he transmits through his work: he tells you about history, he tells you about science," Sobrino notes.

Of history and science

Indeed, Velasco often portrayed more than a landscape; he portrayed history.

Sometimes, that history was long, like the one that appears in his paintings of the Valley of Mexico.

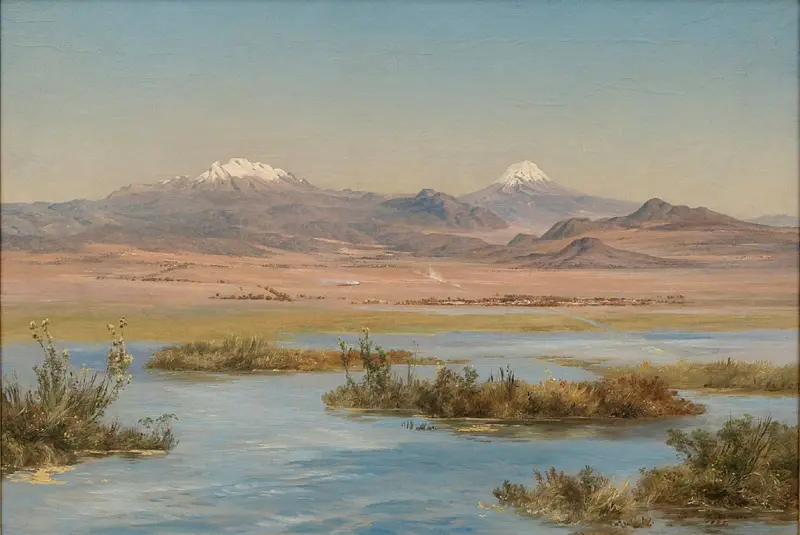

Valley of Mexico, with lagoons, rocks, roads, cities, and mountains

Image source: National Museum of Art, INBAL, Mexico City

Caption: "View of the Valley of Mexico from Santa Isabel Hill," 1875. (Photo: Francisco Kochen)

In the background, modernity: the outlines of the capital of the Republic, next to Lake Texcoco.

Toward the center, the Basilica of Guadalupe, a remnant of the colonial past.

It stands on the slope of Tepeyac Hill where, according to Catholic tradition, the Virgin of Guadalupe appeared to the indigenous Juan Diego in the 16th century, when the Spanish conquest began and traditions blended.

In the foreground, the painting recalls the pre-Hispanic past, featuring an indigenous woman and her two children.

In the 1877 version that appears at the beginning of this article, the indigenous people were replaced with two national symbols: a cactus and an eagle.

According to legend, the Mexica heard the call of the god Huitzilopochtli to seek their promised land, which they would recognize when they saw an eagle perched on a cactus with a snake in its beak.

They found it on an island in the middle of some lagoons in central Mexico, and there they founded Tenochtitlan, today the historic center of Mexico City.

The work became known as Mexico 1877, an indication of its importance to Mexico's national identity.

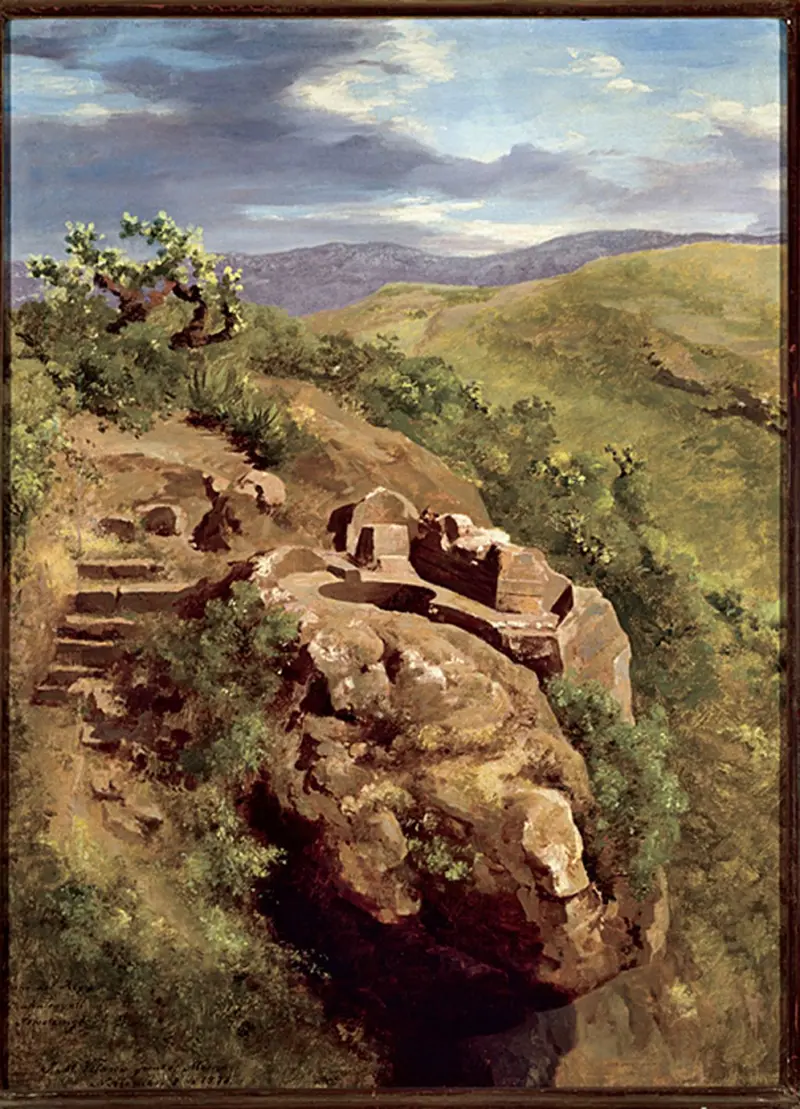

In other paintings, he goes back even further in time.

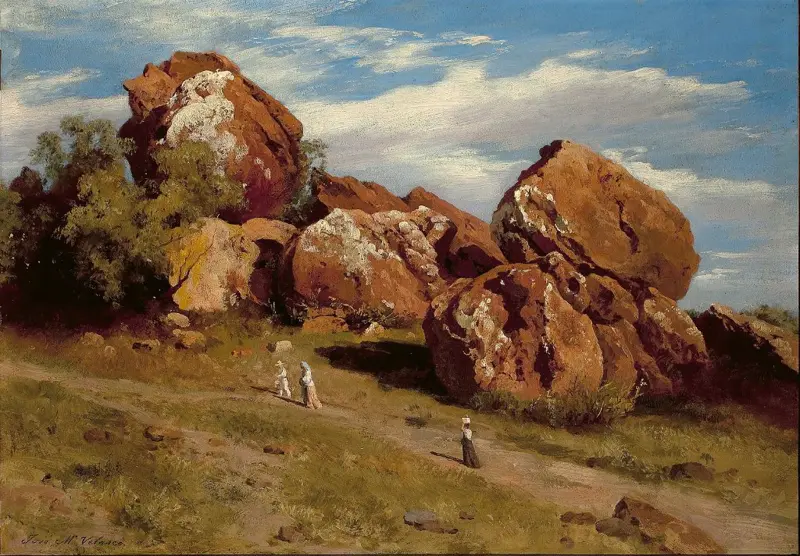

The Atzacoalco Hill, located in the Valley of Mexico, with its characteristic rocks and vegetation.

Image source: Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, Mexico City

Caption: "Rocks of the Atzacoalco Hill," 1874.

"He was aware of recent developments in geology, which indicated that the Earth was millions of years old," Sobrino explains.

"He began to study the way rocks are deposited."

And the Valley of Mexico, so close to his heart, was an ideal place.

"Its base is volcanic, so geologists were very interested in how it formed, and he decided to take a closer look at those incredible glacial erratics."

He portrayed them so well that when he sent one of his paintings to the U.S. in 1876, "the Mexican geologist María Lamberson used it to illustrate her lecture on geology."

Unfinished painting of vegetation and a separate plant

Image source: José María Velasco Archive, Kaluz Museum, Mexico City

Caption: "Mafafa Leaves." (Photo: Jorge Vertiz)

His mastery of rock painting is not surprising considering that, like many artists throughout history, Velasco was deeply interested in science.

At the Academy, he had studied botany, zoology, geography, and architecture, and after graduating, he continued to educate himself in these and other subjects.

This knowledge was poured onto the canvas, producing meticulously accurate images.

A close look reveals details that justify Octavio Paz's use of the term "amphibian," as an artist who lived between art and science.

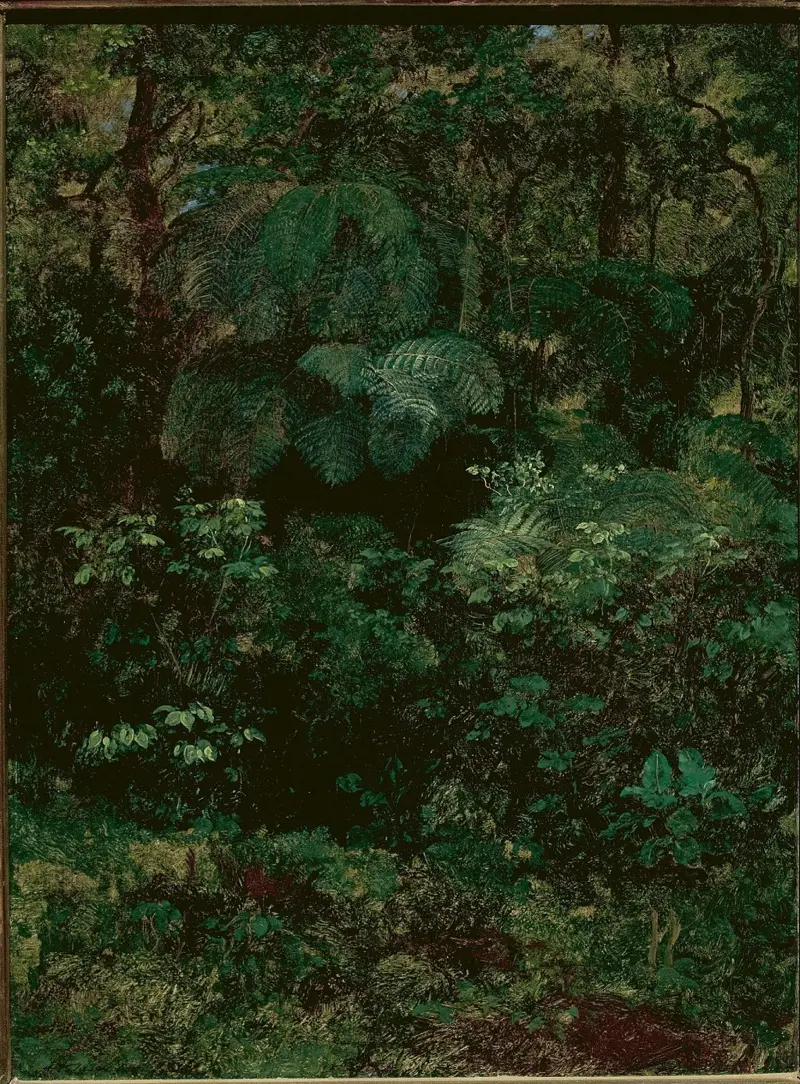

Exuberantly green vegetation

Image source: National Museum of Art, INBAL, Mexico City

Caption: "Bosque de Pacho," 1875.

"Velasco's work combines monumentality and his ability to reproduce the details of rocks, plants, and skies in the finest grain," said writer Adolfo Castañón.

"This could not have happened without training as a scientific draftsman," he added.

His legacy, in fact, extends to the natural and social sciences.

He created a series of prints on the evolution of terrestrial and marine flora and fauna, which became a source of scientific study in his country, leading to his appointment as president of the Mexican Society of Natural History in 1881.

In the end

During the last years of his life, Velasco's heart ached, literally and figuratively.

But neither his physical deterioration nor the sadness that invaded him prevented him from continuing to paint.

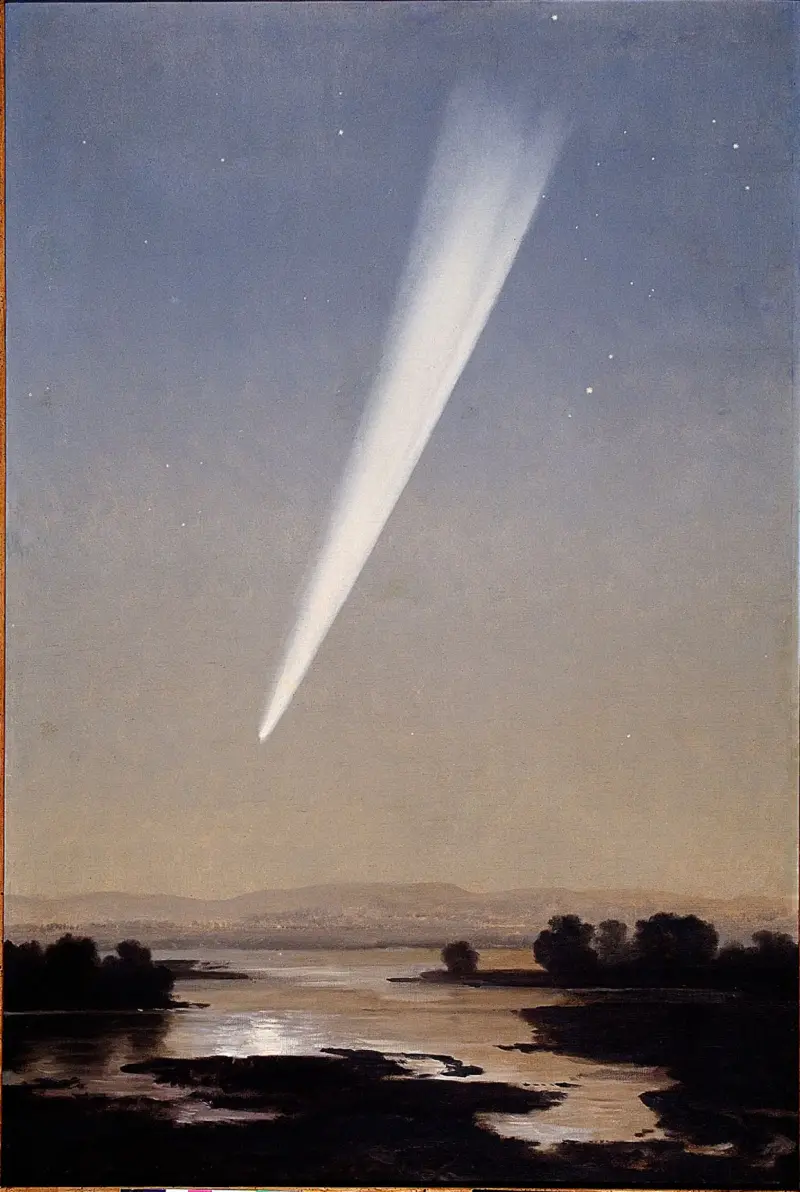

One of the most striking works from that period is "The Great Comet of 1882," which was so bright that it could be observed even during the day, close to the Sun, and was visible to the naked eye in Mexico until February 1883.

Comet in the sky reflected in a lake

Image source: Veracruz Ministry of Culture

Caption: "The Great Comet of 1882," 1910. (Veracruz State Art Museum Collection)

"When he saw it, Velasco made some notes, but he only painted a large version of it in 1910," explains Sobrino.

"It shows in an unusual way how aware he was of the Mexican political situation, since that year marked the end of Porfirio Díaz's regime and the beginning of the Mexican Revolution," he adds.

Furthermore, Halley's Comet was sighted in 1910.

With its white tail reflected in a silver lake that dissolves into shadow, Velasco's comet is a metaphor.

It evokes moments charged with symbolism in Mexico, such as Moctezuma's sighting of the comet in 1517, before the arrival of the Spanish in 1519, connecting long histories and moments of great change, the curator emphasizes.

Moctezuma observing a comet

Image source: Getty Images

Caption: Moctezuma II considered the appearance of a large comet, among other events, to be an ominous omen. (Fray Diego Durán, History of the Indies of New Spain and Islands of Tierra Firme, Vol. I, Chapter LXIII).

He continued painting until the end of his life, although on a smaller scale.

His last works were postcard-sized.

On August 26, 1912, he took one of those 9x14-centimeter cards on which he had been recreating, using oil paint, the images he had stored in his imagination.

And, "according to María Elena Altamirano Piolle, Velasco's great-granddaughter," says Sobrino, "he painted the sky in the morning and died in the afternoon."

Cloud Study

Image source: José María Velasco Archive, Kaluz Museum, Mexico City

Caption: "Cloud Study," 1912. (Photo: Jorge Vertiz)

*The exhibition "José María Velasco, A View of Mexico" will be at the National Gallery in London until August 17, 2025, and from September 27 at The Minneapolis Institute of Art in the US.

online

Click here to read more stories from BBC News Mundo.

Subscribe here to our new newsletter to receive a selection of our best content of the week every Friday.

You can also follow us on YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, X, Facebook, and our WhatsApp channel.

And remember, you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate them.

Source